SET IN STONE: MAURO PERUCCHETTI'S MODERN HEROES

By Peter Frank

Life is never so complex that acts of heroism, individual and societal, can't break through and set, or reset, standards of ethical thinking and moral behavior. But life can be complex enough to obscure what constitutes heroism. Who are the heroes, who are the false demigods, and who are the mad actors presuming themselves heroic but doing the devil's work? Describing heroic nobility is easier than identifying it - and identifying with it is easier than behaving according to its principles.

In his marble sculptures Mauro Perucchetti does not simply ponder these age-old questions, he invites, even seduces, us into contemplating them with him. He throws our false gods and anti-heroes back in our faces. He asks us whom we consider true heroes and whom mere idols. He challenges us - by carving marble, that most obdurate of traditional materials - to consider which heroes are real, and which are mere images, legends, myths.

Perucchetti's ancestors worshiped statues like this, setting a precedent that persisted almost until our time; and the fact that present-day objects of our devotion are overwhelmingly two- (and four-) dimensional does not rob the stone of its ability to compel, certainly not when Perucchetti's figures assume our dimensions as well as occupy our space. Indeed, the relative scarcity of sculpted bodies in contemporary art, especially in public space, gives an exotic flair to the realness of these marble apparitions - and, one could project, portends a new era of the solid.

Even now, three-dimensional imaging is rapidly bringing that era to fruition. But Perucchetti's work involves no such technology. He has repurposed a millennia-old method to modern artmaking, in order to give bite to its expression, a bite both ironic and prophetic, ethical and aesthetic. To hand-fashion marble in this day and age is to transcend anachronism and superannuation; rather, it is to invoke the very condition of idealism, pointing as it does at a model of reasoning and decorum so antiquated that it just might be new again.

At first glance, seeing Batman and Superman - ultra-post-modern versions of heroes - rendered in an ancient stone, and enacting hyperbolic, and homoerotic, gestures of salvation Michelangelo would recognize, seems a thorough capitulation to the lens of modern civilization. But snark actually loses here to passion. Such literalized, if frozen, drama vindicates rather than vitiates the innocent pretenses of cosplay participants, suggesting their imaginary heroes can take form in space as well as time, and in the most exquisite of materials. The more dubious heroics, and even more certain sexual frisson, that pairs Catwoman with Medusa asks us to consider both Perseus' nemesis and Batman's frenemy as complex personae, representing not fearsome evil but fear itself, the result of psyches damaged by trauma and injustice.

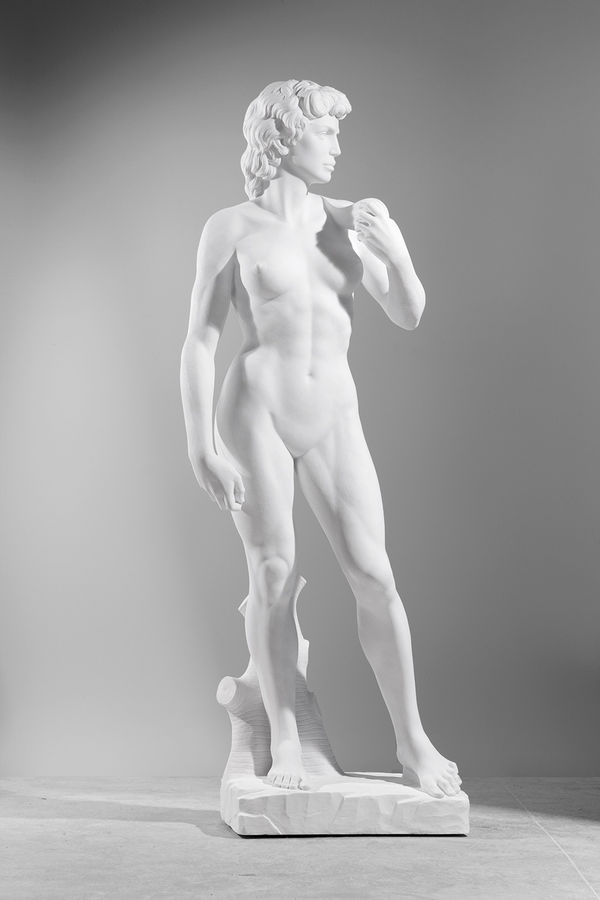

The duo of superhuman, yet compromised, women reveals a feminist subtext among Perucchetti's Modern Heroes, one that repositions the female with regard to her pedestal. She is no longer passive. She may make grave errors, as The Role Model does, but they are errors of commission; she is responsible for her actions and their victim, no longer the victim of men. Conversely, Perucchetti heroicizes woman by having her usurp man's pedestal, subjecting David to a Tiresian (not just surgical) conversion. The Tribute to Women assumes the original's dynamic poise, conflating the subject of heroic action with the object of desire. The unseen Goliath will be toppled, in a victory for women everywhere.

As we do, Perucchetti reads constantly of women fighting back all over the world. And he reads of men driven insane by their own circumstances, their medications, their fantasies. His version of Rodin's Thinker modifies the original only slightly, but drops it thereby into the maelstrom of contemporary angst. Perhaps Perucchetti is asking would-be murderers and suicides to contemplate their actions; or perhaps he's depicting (one of) them brooding over the impending, or even realized, deed. Whatever the narrative here, it is not that of the original's existential speculation - or, if it is, it is of such speculation endowed with deadly force, the ultimate anti-heroic act. We can perhaps bear anti-heroics of the type indulged in by the couple bathetically taking advantage of being Home Alone (Miss Piggy, no feminist she, is a hero mostly in her own mind); but The Thinker hits close to home.

The Sin of Man - and Woman - gets measured against a higher power, whether the Word of God or the connivances of gods. And of course, s/he is going to be found wanting; whether or not sin is original, it is eternal. Mauro Perucchetti ponders this metaphysical bind in his marble sculptures, employing a medium as timeworn as the stories of sin and redemption themselves. Maybe the most ironic thing about the series "Modern Heroes" is its title. Behind those costumes, those poses, that delicious and impervious material are beings that are neither heroes nor modern, just modernized. Ecce homo.

Los Angeles, June 2014

STONED AGAIN: NEW MARBLES BY MAURO PERUCCHETTI

By Peter Frank

It has been over the past few years that Mauro Perucchetti has fabricated this small but potent sequence of cultural references, a sequence that at once conflicts with and depends on the guidelines-or at least the tropes - of classic sculpture in marble. Having realized such an at-once elegant and parodic series, Perucchetti has recently turned his sights to the realization of more recondite sculptures. They are not harder to understand in their contemporary cultural contexts, to be sure, but they are harder to understand in the context of marble and its history. This slippage in context is precisely what gives them their edge, what hones, amplifies, and subverts their meanings to the point where we have to re-examine what they have meant in the first place, to us and to the civilization we sustain.

Damned if You Do, Damned if You Don't brings together four separate sculptural units on a fifth, a base whose blackness sets off the whiteness of the units placed thereupon. The white unit stake the shape of hands, hands in the act(s) of moving their fingers into crucial positions. The three reclining hands form their two most prominent fingers into the familiar "V" sign - a gesture first employed by Anglo-American forces during World War II as (literal) shorthand for "victory" and later adopted (perhaps ironically) by young people protesting the war in Vietnam (the sign again originating in the United States and adopted quickly by protestors around the world). Despite repeated attempts at co-optation by the very forces they oppose, anti-governmental protestors have retained the gesture. But their less political cohorts, at least in the United Kingdom, have further ironized the "V," converting it in to a rude gesture of defiance - to the point where it has become almost synonymous with the signal given by the one "standing" hand in Damned if You Do. That geste is the least beau of all, a one-digit salute whose sexual origins and resulting offensive meaning are globally recognized.

Perucchetti has left the elaborate hand speech of his native Italy, American Sign Language, and gansignaling for another day; he is more concerned here with digital semiotics gone viral. 18th of October 1968, A Date I Still Remember - an unusual combination of marble and leather, and pointedly black on black - memorializes a moment of protest in which no "bird" was flipped, but might as well have been. Two African-American athletes, having won first and third places in an Olympic race in Mexico City, raised their fisted arms in a black-power salute, affronting their government with a show of separatism. Perucchetti has "translated" their gesture in to a yet clearer expression of rejection. 18th of October contrasts significantly with Damned if You Do, beyond its reversal of color and expansion in size. While the larger sculpture commemorates a specific event that still resonates with Perucchetti - as it does for many others - almost a half-century since, the smaller reflects on a more general condition. 18th of October would seem to celebrate the effectiveness of protest; despite the outcry and subsequent censure of the athletes who raised their fists (getting treated as if they had extended their middle fingers), the gesture retains its sway. But most protest, polite and impolite alike, is quashed by its targets, governmental and/or corporate, cut off at least at the wrist by a power elite that, especially these days, has no compunction about destroying, not just quieting, its popular (as well as official) opposition.

The other two new marble works are rather more forth right in their meaning, or at least their imagery. The Engraved Marble Dollar is just that, a replication so faithful to the paper original - right down to the green seal and grayed serial numbers - that only its absurdly large scale and heft keep its inventor out of prison for counterfeiting. This is no paper weight: It is a representation, in size and in density, of America's economic clout. Conversely, Fiato d' Artista proposes a circumstance that is, by inference, lighter than air. A marble replica of a "whoopee cushion," the Fiato renders the original gag physically impossible to realize, but in doing so reformulates it as a conceptual proposal - and, not accidentally, an elegant homage to Perucchetti's proto conceptual country man, Piero Manzoni, who sold balloons filled with "artist's breath" and cans of "artist's shit." Here, in a loving reversal of Manzoni's impermanent offerings, Mauro Perucchetti has given the least aspect of the human body - and a similarly coarse mimicking device - the dignity of permanence. Arse longa…

Los Angeles, January 2015

-

MODERN HEROES, 2009Hand-carved white marble190 x 195 x 75 cm (74.75 x 76.75 x 29.5 inches)

MODERN HEROES, 2009Hand-carved white marble190 x 195 x 75 cm (74.75 x 76.75 x 29.5 inches)

-

MICHELANGELO MY TRIBUTE TO WOMEN, 2020Hand-carved white marble174 x 62 x 42 cm (68.5 x 24.75 x 16.5 inches)

MICHELANGELO MY TRIBUTE TO WOMEN, 2020Hand-carved white marble174 x 62 x 42 cm (68.5 x 24.75 x 16.5 inches) -

MODERN HEROES II, 2011Hand -carved white marble107 x 55 x 45 cm (42.8 x 22 x 18 inches)

MODERN HEROES II, 2011Hand -carved white marble107 x 55 x 45 cm (42.8 x 22 x 18 inches) -

THE THINKER, 2011Hand-carved white marble90 x 67 x 45 cm (36 x 25.6 x 18 inches)

THE THINKER, 2011Hand-carved white marble90 x 67 x 45 cm (36 x 25.6 x 18 inches) -

THE ROLE MODEL, 2011Hand-carved white marble65 x 90 x 60 cm (26 x 36 x 24 inches)

THE ROLE MODEL, 2011Hand-carved white marble65 x 90 x 60 cm (26 x 36 x 24 inches)

-

A.I., 2012Hand-carved white marble70 x 60 x 30 cm (27.5 x 23.6 x 11.8 inches)

A.I., 2012Hand-carved white marble70 x 60 x 30 cm (27.5 x 23.6 x 11.8 inches) -

DAMNED IF YOU DO DAMNED IF YOU DON'T, 2014Hand-carved white marble on black marble base28 x 38 x 30 cm (11 x 15 x 11.8 inches)

DAMNED IF YOU DO DAMNED IF YOU DON'T, 2014Hand-carved white marble on black marble base28 x 38 x 30 cm (11 x 15 x 11.8 inches) -

THE WORD OF GOD THE SIN OF MAN, 2011Hand-carved white marble67 x 64 x 45 cm (26.8 x 25.6 x 18 inches)

THE WORD OF GOD THE SIN OF MAN, 2011Hand-carved white marble67 x 64 x 45 cm (26.8 x 25.6 x 18 inches) -

A MONUMENT TO THE DOLLAR, 2014Engraved Carrara marble65 x 153 x 2 cm (25.6 x 60.2 x 0.8 inches)

A MONUMENT TO THE DOLLAR, 2014Engraved Carrara marble65 x 153 x 2 cm (25.6 x 60.2 x 0.8 inches) -

FIATO D'ARTISTA, 2014Marble composite on black granite base20 x 25 x 30 cm (7.9 x 9.8 x 11.8 inches)

FIATO D'ARTISTA, 2014Marble composite on black granite base20 x 25 x 30 cm (7.9 x 9.8 x 11.8 inches)

-

OCTOBER 16, 1968 A DATE I STILL REMEMBER, 2014Hand-carved black marble on black granite base31 x 28 x 28 cm (12.2 x 11 x 11 inches)

OCTOBER 16, 1968 A DATE I STILL REMEMBER, 2014Hand-carved black marble on black granite base31 x 28 x 28 cm (12.2 x 11 x 11 inches)